Greeting Other Dogs. What is the Etiquette?

Post Date:

December 6, 2023

(Date Last Modified: November 13, 2025)

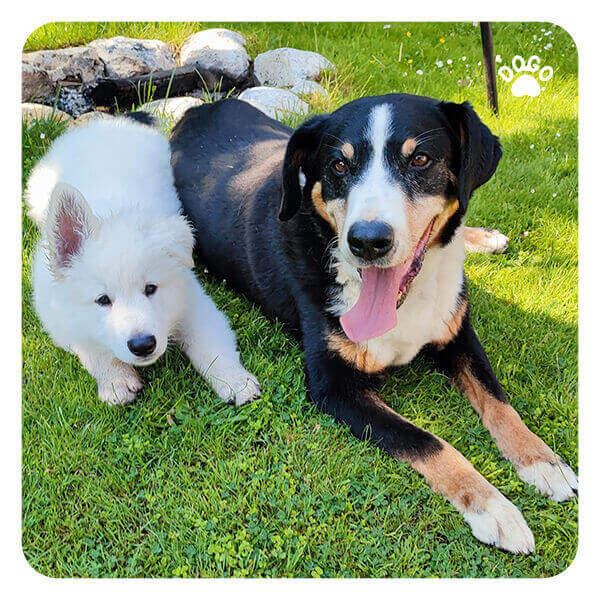

Greeting other dogs is a routine part of canine life that affects safety, comfort, and social outcomes for both animals and people.

Why Dog Greeting Etiquette Matters

Proper greeting behavior reduces the likelihood of injury and stress by allowing dogs to exchange signals and assess one another calmly; allow 3–5 seconds for an initial sniff before changing proximity or posture.[1] Respectful greetings also help owners maintain public safety and community norms by lowering the chance that a brief misunderstanding escalates into a fight or a bite.

Reading Canine Body Language

Canine signals fall broadly into calming signals, neutral interest signals, and escalation cues; learning to differentiate these categories helps an owner decide whether to let an interaction proceed. Watch tail carriage and movement: a loosely wagging tail that moves low and slow typically indicates relaxed interest, whereas a very high, stiff tail or fast, tense wag can be part of a threat display. Look at ear position and facial tension: ears forward with a hard stare or prolonged lip lifting are frequent precursors to aggression. If calming signals such as yawns, soft blinks, or head turns are absent and you observe sustained stiff posture or a growl lasting 2 seconds or longer, treat the encounter as potentially escalating and increase distance.[2]

| Signal | Likely meaning | Recommended owner response |

|---|---|---|

| Loose body, soft mouth | Relaxed or playful interest | Allow calm sniffing; observe for escalation |

| Yawning, soft blink | Self-calming or calming offer | Give space; reward calm behavior |

| Stiff posture, direct stare | High arousal or threat | Increase distance; end greeting if needed |

| Rooting or mounting | Bounded arousal or dominance attempt | Interrupt calmly and separate |

Owner Awareness and Consent

Owners are responsible for managing interactions and should always seek permission before allowing their dog to approach another person’s animal. Clear, calm communication sets expectations: tell the other owner whether your dog is comfortable with close sniffing, needs space, or prefers no contact. Be prepared to remove your dog promptly if the other animal shows stress or if either handler feels unsafe. Practical steps include greeting handlers first, asking simple questions about temperament, and ensuring both dogs remain physically under control during any initial contact.

- Always ask before allowing an approach and accept a negative reply without pressuring the other owner.

- Describe your dog’s cues and limits briefly and honestly so the other handler knows what to watch for.

- Be ready to disengage immediately if either dog stiffens, growls, or repeatedly shows avoidance signals.

Approaching Another Dog Safely

Avoid direct head-on approaches and prolonged staring; instead use an angled, relaxed body position and a soft tone to reduce perceived threat. Stop 2–3 feet (0.6–0.9 m) away and observe whether both dogs show relaxed interest before allowing closer contact; if either dog tenses, hold position or back away slowly.[3] Let the dogs decide whether to meet and control the distance rather than forcing nose-to-nose contact.

Leash Etiquette and When to Intervene

Leashes change the mechanics of greetings because restraint can amplify tension and prevent normal escape behaviors. Keep a relaxed length of leash so the dog can move fluidly; avoid jerking or tight short leads that heighten stress. On walks, manage brief on-leash sniff opportunities as short, supervised exchanges and limit them to avoid building arousal; for example, brief sniff windows and walk-by introductions work better than forced stationary meetings. If the leash becomes an instrument of control during an approach—if it is taut and the dog is straining—separate and reposition to let both animals settle before re-engaging.[4]

Appropriate Greeting Behaviors

A normal greeting sequence commonly follows a short investigative sniffing pattern, limited mutual circling, and either disengagement or an invitation to play. Typical sniffing sequences are brief, often lasting about 3–10 seconds before one dog moves away or signals continued interest.[5] Discouraged actions include face-to-face lunging, forced physical contact, and hugging or restraining a dog in place; these can be misread as threats. Recognize escalation signs such as piloerection over the back, repeated hard stares, repeated snarling, or quick lunges, and end the greeting early if such cues appear.

When Greetings Should Be Prevented

There are contexts where a greeting should not occur: when either dog is ill, recovering from surgery, or clearly injured, in which case avoid contact until cleared by a veterinarian—typically wait at least 10–14 days post-operatively or until the vet confirms it is safe.[6] Other reasons to prevent greetings include recent or ongoing resource-guarding behavior, intact females in heat, known histories of aggression, or crowded, high-distraction environments where the risk of escalation increases.

Managing Reactive or Anxious Dogs

For dogs that are anxious or reactive, maintain distance and use positive markers and safe zones to allow the animal to observe without being overwhelmed. Start counter-conditioning and desensitization at a distance where the dog exhibits minimal stress, and use short, predictable exposures of 1–2 minutes that reward calm, non-reactive behavior before gradually decreasing distance over many repetitions. If a dog’s reactivity persists or escalates despite structured, consistent work, consult a qualified veterinary behaviorist or certified trainer for an individualized plan and, when appropriate, medical assessment.

Socialization and Training to Teach Good Greetings

Early, controlled socialization builds the foundation for polite greetings. Puppies are particularly receptive to positive social experiences during their primary socialization window; aim for varied, calm exposures to different dogs and people while supervising closely. Reinforce calm behaviors such as sitting and loose body posture with treats and praise, and teach reliable cues—recall, “leave it,” or a short timeout—to interrupt interactions when needed. Use structured playdates and supervised group classes to practice greetings in a managed setting where handlers can intervene quickly and consistently reinforce desirable responses.

Thoughtful owner management, attention to canine signals, and proactive training reduce risk and help dogs learn to meet one another with confidence and calm.

Practical Training Plan Example

Begin with very short, predictable sessions: 3–5 minutes, 2–4 times per day, focusing on distance work where the dog notices another dog but does not react; reward calm attention with a high-value treat or marker when the dog maintains loose posture for 3–5 seconds.[5] Progress only when the dog has shown calm responses in at least 8–10 successful repetitions at the current distance; if a session produces any signs of escalation, return to the previous distance and repeat the lower-intensity steps for another 3–5 sessions before trying to advance.[4]

Use clear, simple cues the dog already knows—recall and “leave it” are particularly useful—then pair those cues with predictable rewards so the dog learns that focusing on the handler brings access to preferred outcomes instead of forced contact. If introducing a food-based counter-conditioning protocol, place treats in the handler’s hand and deliver one treat every 2–4 seconds while the dog observes the other animal at the comfortable distance; gradually shorten the treat interval only after the dog consistently exhibits relaxed body language during 10–15 minute practice blocks.[1]

When scheduling supervised playdates as part of socialization, limit each session to a maximum of 20–30 minutes for dogs still learning polite greetings, and include at least one short break of 5–10 minutes every 10–15 minutes to prevent cumulative arousal from driving escalation.[6]

Emergency Steps for Rapid Escalation

If an interaction escalates suddenly—characterized by sustained snarling, quick lunges, or physical contact—prioritize separation while minimizing the chance of accidental injury. Create space by turning both dogs away and moving them at least 10–15 feet (3–4.5 m) apart before attempting to calm them; avoid grabbing collars or placing hands near faces, which increases bite risk.[2]

When separation requires physical intervention, use barriers where possible (a car door, a fence gate, or an object to block access) and call for assistance from another responsible adult rather than trying to restrain both dogs alone; coordinated removal by two handlers reduces handling time and lowers the chance of injury to people and animals. After separation, check each dog for injuries and seek veterinary care if there are any wounds deeper than 1/8 inch (3 mm) or any puncture marks, as those often require professional cleaning and assessment.[1]

Document the sequence of events immediately—what prompted the approach, the behaviors observed, and the handlers’ actions—so a trainer or behaviorist can assess triggers and design follow-up plans. If either dog bites a person, follow local public-safety reporting rules promptly and seek both medical and veterinary input, since human wounds may require prophylactic care and the incident often factors into future management plans.[2]

Measuring Progress and When to Seek Expert Help

Establish objective, measurable goals such as “dog holds loose gaze and accepts treats at 10 feet (3 m) from another dog in 8 of 10 trials” or “dog refrains from lunging for 30 consecutive seconds during a graded approach” to evaluate whether training is effective; record sessions to monitor subtle changes in posture or arousal that may not be obvious in real time.[5]

If a dog’s reactivity includes repeated attempts to bite, escalation despite gradual desensitization, or anxiety symptoms that generalize to multiple contexts, consult a veterinary behaviorist or a certified applied animal behaviorist; many professionals recommend involvement when progress stalls after 6–8 weeks of consistent, properly executed training or when risk to people or other animals remains elevated.[4]

Veterinary evaluation is indicated when greeting problems are associated with sudden behavioral changes, pain, or medical contributors such as hypothyroidism or neurological issues; a primary-care veterinarian or specialist can often perform screening tests and suggest whether adjunct medical management might support behavioral modification efforts.[1]

Practical Handler Scripts and Phrases

Use short, neutral phrases when approaching another handler: ask “May I?” and state your dog’s preference briefly, for example “He’s shy, prefers distance.” If you are the responding owner and prefer no contact, say “Thank you, we’re not meeting today.” Consistent language reduces misunderstanding and decreases the chance that handlers inadvertently allow approaches that will stress one or both dogs.

When rescuing a tense situation, give calm, prescriptive instructions: “Back away slowly,” “Turn your dog,” or “Leash up and move to the car.” Avoid emotional language like yelling or scolding the dogs as that often elevates arousal and complicates recovery; instead, focus on actions that change the dogs’ geometry and allow breathing-room immediately.[3]

Finally, prioritize prevention: proactive communication, training to reinforce calm responses, and community norms that respect owner consent are more effective than reacting after problems occur. Regular, controlled exposures and clear owner agreements make polite greetings more likely and safer for everyone involved.